Apologies for the delay on this post, the internet in the town where I started and ended my tour had no wi-fi, and the connection at the internet cafés was so slow my Gmail would barely load. My plan was to wait until I crossed the border to Argentina to get this post, mostly of photos and a few descriptions, live. My laptop, however, has since died, so I have no way of uploading my own photos. These words will have to do instead, with hopes that I can maybe get my computer up and running soon.

Edited: My computer is back from the dead! At least long enough to let me get these photos up, so you’re in luck!

My tour of southwestern Bolivia consisted of days so long and so jam-packed that at the end of it all, it was hard to believe I´d only been gone for 4 days, and not 4 weeks. Despite the exhaustion from not sleeping properly at high altitudes and spending hours on end in a not-so-comfortable jeep, I had a fabulous trip, met some wonderful people who actually changed the course of my trip (more on that later), and saw some of the most incredible scenery I´ve ever laid eyes on.

There were hours where I looked out of the jeep window and the landscape looked so foreign that I swore I´d been transported to Mars, and other moments where it looked as though I was back at Arches National Park in Utah. The Salar de Uyuni, the highlight of the tour, was our last stop on the fourth day, but we spent the third night at it´s edge. Walking out onto the endless expanse of salt was more humbling than I can describe. And even though our 4 AM wakeup call on day four was just as painful as my 4 AM Machu Picchu wakeup call nearly six months ago, the sunrise I witnessed was so different, it literally took my breath away.

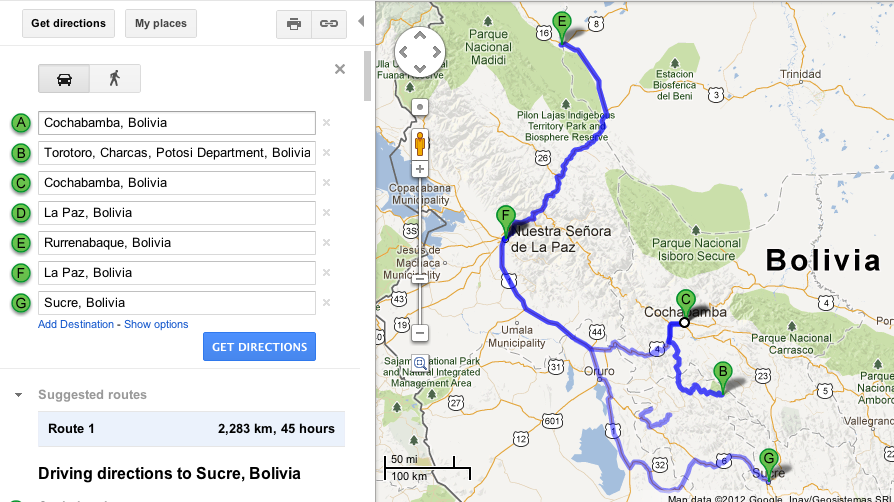

Most people head west from Potosi (where I did the mine tour) to Uyuni, where the majority of the 3 day/2 night tours of the Salar de Uyuni Salt Flats start. I´d been given advice, however, that starting from Tupiza, an equally small town that is directly south of Potosi, is a lesser known, but much better option. From Tupiza, the tour is four days and three nights, the landscape surrounding the town is beautiful, you drive through a completely different national park, end with the salt flats instead of begin with them, and the tour quality is supposed to be higher. All of this advice proved true, and I am incredibly thankful I started from Tupiza instead.

- On the night bus from Potosi to Tupiza, I ran into Vincent, one of the guys on the same mine tour I´d done earlier in the day. When we got off the bus at 4 AM in Tupiza, we decided to check in at the same hostel and research Salar tours together the next morning. A few hours later as we wandered through town, we ran into Anthony and David — two Australian guys also on our tour in Potosi — and it turned out all four of us were staying at the same hostel/tour agency and had booked the same 4 day tour leaving the next day. Yet another small-world South America run in! As happy as I am to be traveling on my own, I was glad to know I´d have some familiar faces on my tour.

- The day before we left Tupiza, Vincent and I took a 3 hour horseback ride in the red-rock valley near Tupiza. Although our horses random, un-announced galloping was a little bit overwhelming, the scenery was beautiful, and I immediately fell in love with southwestern Bolivia. The naturally carved red rocks, low-growing green brush, and mountain studded horizon reminded me of a more spectacular version of the southwestern US, and I couldn´t get enough.

- Our immediate tour group consisted of two jeeps. I spent countless hours bouncing along dirt roads with Eduardo the driver, Irena the cook, Vincent, Stephanie and Isabelle, French-speaking sisters from Switzerland. The other jeep shared our cook, and was headed by Edson the driver and Sergio, our English volunteer tour guide. Laura from Australia, Brian from Ireland, and Sophie and Daniel, a couple from Switzerland, filled the four back seats. There were three other jeeps from the same tour agency that we saw along the route and stayed at the same hostels with, including Anthony and David, my Australian buddies.

- Toward the end of our first day on the road, we had just climbed back into the jeeps after a stop at an eerily abandoned ghost town. As we cruised away, our jeep began shaking and rattling, but not from the rocky, dirt road we were driving on. We were being pelted with huge chunks of hail. Thunder rumbled so loudly we were all slightly startled, and the lightning streaked so brightly it lit up the entire sky — at one point we even saw smoke rise as the currents hit the mountains ahead of us. Amazingly, we drove straight through the storm and into the pueblo where we´d be spending our first night, and by then all was calm. In fact, the sky was clear enough that we were able to climb up on a ridge behind the town to watch the sun set behind the grey clouds in the distance.

-

Throughout the tour, we stopped at a half-dozen alien-looking lagoons filled with bright, strangely colored water and hundreds of gorgeous pink flamingos. My favorites were Laguna Colorado, a bright red lake that gets its stunning coloring from red plankton, and Laguna Hedionda, a stunning bright turquoise lake rimmed in white minerals and surrounded by picture-perfect mountains that were reflected in the clear, still water.

-

At some point on day two, the landscape changed drastically and it was like we´d suddenly landed on Mars. Flat red, rocky expanses of nothingness stretched out before us and black volcanoes with bright yellow, white, and red tops captivated the four of us as our jeep zoomed past them. I wasn´t surprised to find out later that that specific area of the Bolivian desert is actually used by NASA to test space rovers because the wind conditions and rocky landscape mimic those of Mars.

-

On our second night, I braved the miserably cold air to stand outside and stare at the stars. I can´t remember seeing such a bright sky since my Camp Tawonga days, and watching a shooting star streak through the darkness reminded me of how much I absolutely love the night sky. I had one of those cheesy travel moments, where I couldn´t have been more thankful that I quit my job and made myself crazy for a few months so I could be standing in that spot, seeing the beauty of the world. It just solidified how worth it this has all been, despite the ups and downs of the last few weeks.

-

On day three, the landscape turned flat and the mirage on the horizon appeared. The sun reflecting off the salt, stretching out for hundreds of miles in front of us, made the salt flats look like a perfectly mirrored lake, and we were all convinced it was actually covered in water until our guide corrected us. Once we put our things down at the hostel, we walked a half hour out onto the edge of the salar. Its expansiveness was humbling, but in a completely different way than anything I´ve seen on this trip thus far. Incan ruins, mountain ranges, cloud rainforests, pelican-dotted beaches… they all seemed so far away, and so drastically different.

- Our last stop after the salt flats and before the town of Uyuni, where our tour officially ended, was a massive train cemetery, where old, rusted British trains had been abandoned. Unfortunately, my camera battery died shortly after our arrival, but I could have easily stayed there all day with my DSLR — the rusting iron, graffiti-covered cars contrasted with the hilly background was a photographers paradise.

Overall, I had a fabulous trip. I wish there was a bit more walking and a bit less sitting in the jeep, but as everyone had told me to expect, the Salar truly was spectacular.

My original plan was to get out of the jeep in Uyuni and immediately arrange a transport out to San Pedro de Atacama in Chile. But it turned out my plans for Argentina overlapped with Vincent´s and Sergio´s and I decided I wanted to have some travel company for a bit, so I ended up coming back to Tupiza to relax, wait for Sergio to finish his volunteer gig, and the two of us made our way down to Salta yesterday for a few days. After Salta, I have yet to make up my mind whether I´ll go out to San Pedro like I´d originally planned and then hightail it to Cordoba to meet Vincent, or keep heading south on my own to explore some smaller towns and then wait for Vincent.

My OCD tendancies are hating my indecision right now, but the other half of me is so thrilled that my vacation has warped and changed so beautifully just because I made instinctive decisions to do exactly what I wanted from moment to moment. Not having a solidified plan has been a wonderful thing!

And now, cross your fingers that my nearly seven-year old macbook wakes up from her deep sleep long enough to let me post pictures!